Julie A. Sellers

Some Place of the Sun

A Pandemic Cento*

I have been one acquainted with the night,

lost as a candle lit at noon,

lost as a snowflake in the sea.

The times are nightfall, look their light grows less.

What if a dawn of a doom of a dream

bites this universe in two?

This is the secret of despair

and fault of novel germs.

Things fall apart, the center cannot hold.

It was here in my home

that a butterfly happened to wing by

like a ship that carried me along

through the deadliest storm,

admonished me the unloved year

would turn on its hinge that night.

No one but Night, with tears on her dark face,

watches beside me in this windy place

in fields where roses fade,

back in a time made simple by the loss

of detail, burned, dissolved, and broken off.

Artificial lamps

make strange shadows

and bow and accept the end.

The last of last words spoken is Good-bye.

Even a map cannot show you

the way back to a place

that no longer exists.

But still, like air, I’ll rise

when I behold, upon the night’s starred face,

this dream the world is having about itself,

and death shall have no dominion.

Even night will blossom as the rose.

Not tonight but tomorrow,

forth I wander, forth I must,

and drink of life again.

I speak this poem now with grave and level voice,

leaving behind nights of terror and fear

to fling my arms wide

in some place of the sun.

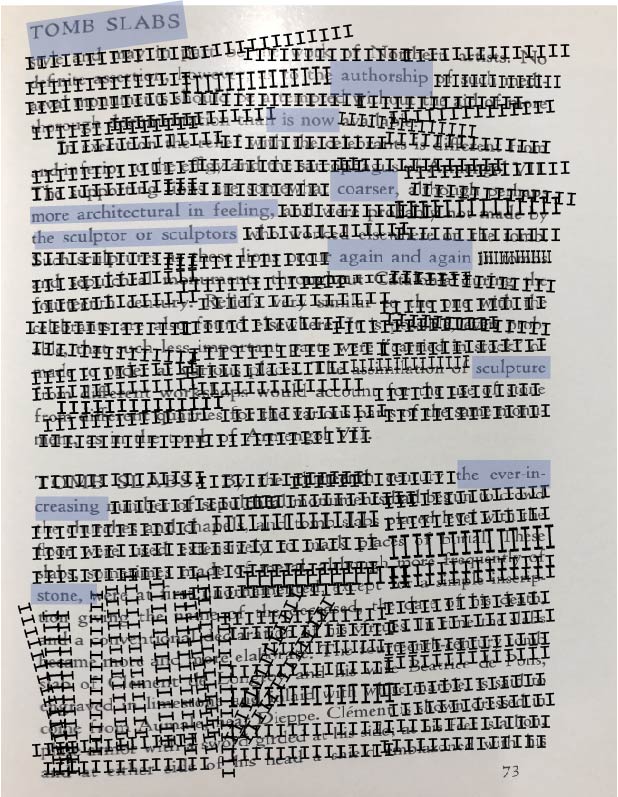

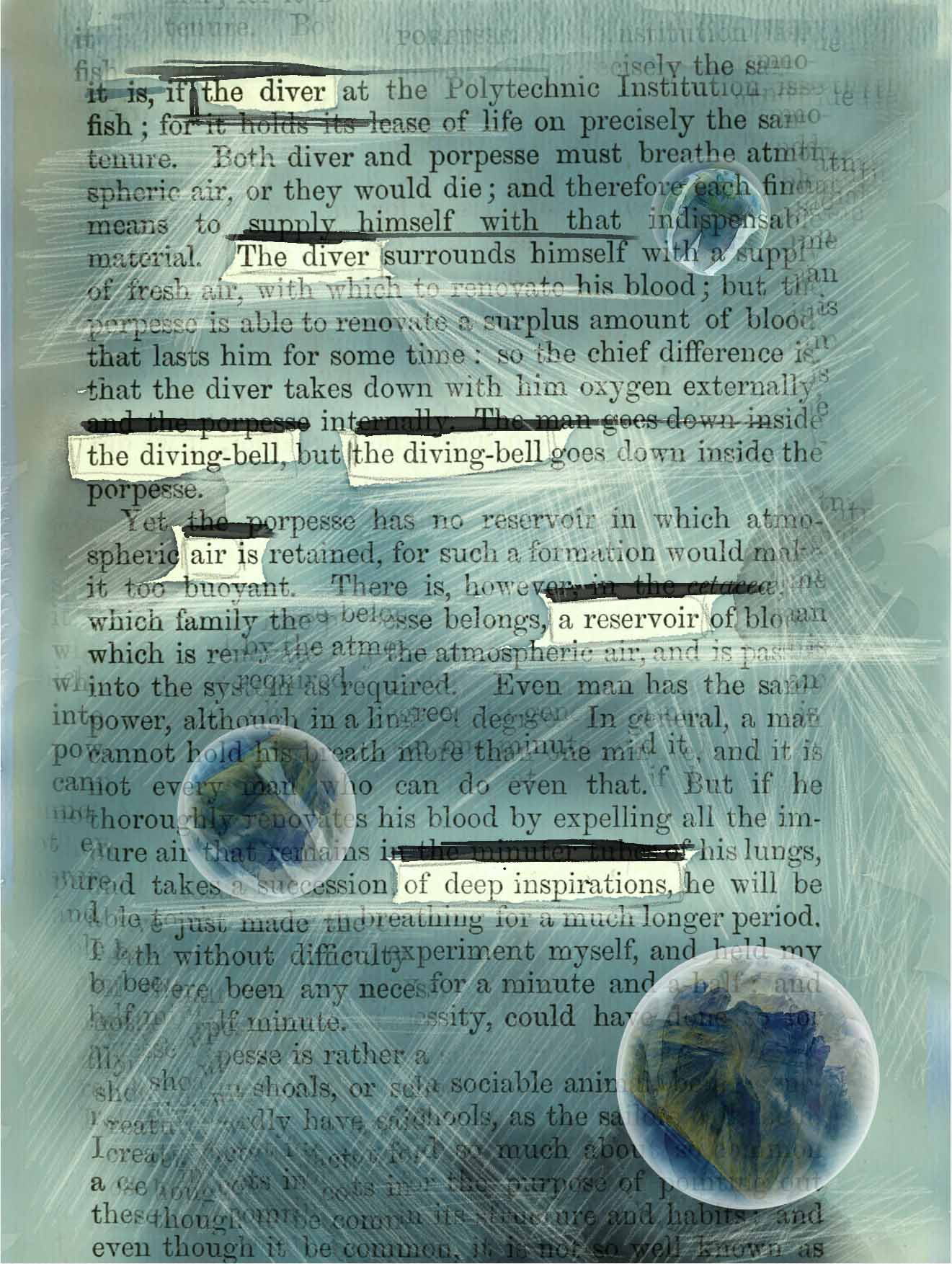

Source & Method

This pandemic Cento interweaves lines from a variety of poets whose verse resonated with me during this challenging time. I typed the lines that I found particularly poignant, printed them, cut them apart, and rearranged them to create my expression of life during the pandemic.

Sources by line number:

1. Robert Frost, “Acquainted with the Night”

2. Sara Teasdale, “I am Not Yours”

3. Sara Teasdale, “I am Not Yours”

4. George Manley Hopkins, “The Times are Nightfall, Look their Light

Grows Less”

5. e.e. cummings, “what if a much of a which of wind”

6. e.e. cummings, “what if a much of a which of wind”

7. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, “Snowflakes”

8. Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Terminus”

9. William Butler Yeats, “The Second Coming”

10. Jesús Papoleto Meléndez, “of a butterfly in el barrio or a stranger

in paradise”

11. Jesús Papoleto Meléndez, “of a butterfly in el barrio or a stranger

in paradise”

12. Rainer Maria Rilke, “I Am Much Too Alone in This World, Yet Not

Alone Enough”

13. Rainer Maria Rilke, “I Am Much Too Alone in This World, Yet Not

Alone Enough”

14. Stanley Kunitz, “End of Summer”

15. Stanley Kunitz, “End of Summer”

16. Edna St. Vincent Millay, “Night is My Sister”

17. Edna St. Vincent Millay, “Night is My Sister”

18. A. E. Housman, “With Rue My Heart is Laden”

19. Robert Frost, “Directive”

20. Robert Frost, “Directive”

21. Pedro Pietri, “do not let”

22. Pedro Pietri, “do not let”

23. Robert Frost, “Reluctance”

24. Walter de la Mare, “Good-bye”

25. Sandra M. Castillo, “Christmas, 1970”

26. Sandra M. Castillo, “Christmas, 1970”

27. Sandra M. Castillo, “Christmas, 1970”

28. Maya Angelou, “Still I Rise”

29. John Keats, “When I Have Fears”

30. William Stafford, “Vocation”

31. Dylan Thomas, “And Death Shall Have No Dominion”

32. John Masefield, “On Growing Old”

33. Miguel Algarín, “Not Tonight but Tomorrow”

34. A. E. Housman, “When Green Buds Hang in the Elm”

35. A. E. Housman, “When Green Buds Hang in the Elm”

36. Archibald MacLeish, “Immortal Autumn”

37. Maya Angelou, “Still I Rise”

38. Langston Hughes, “Dream Variations”

39. Langston Hughes, “Dream Variations”

Julie A. Sellers was the Kansas Authors Club’s 2020 Prose Writer of the Year. She is the author of Kindred Verse: Poems Inspired by Anne of Green Gables (2021).